A language is, famously, a “dialect with an army and a navy.” Which is to say that languages, and how they are categorized, are always subject to ideological influence. As a result, these linguistic boundaries are far more fluid than they may appear at first glance. The question of “is this a language or dialect?” is primarily a political rather than linguistic one.

Language as National Identity

The idea of a national people being defined by a national language is a comparatively new one. Across many parts of the world, it was common to switch frequently between languages without strongly identifying with any one in particular. You might have used one language with your parents, another at the market, and yet another in spiritual worship. Latin, as one notable example, was reserved exclusively for scholarly and religious pursuits.

Yet today, we take it for granted that language is seen as a marker of belonging to a particular nation of people, just like flags, currency, and passports. This is at the crux of these “language vs. dialect” complications.

Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, Serbian: One Language or Four?

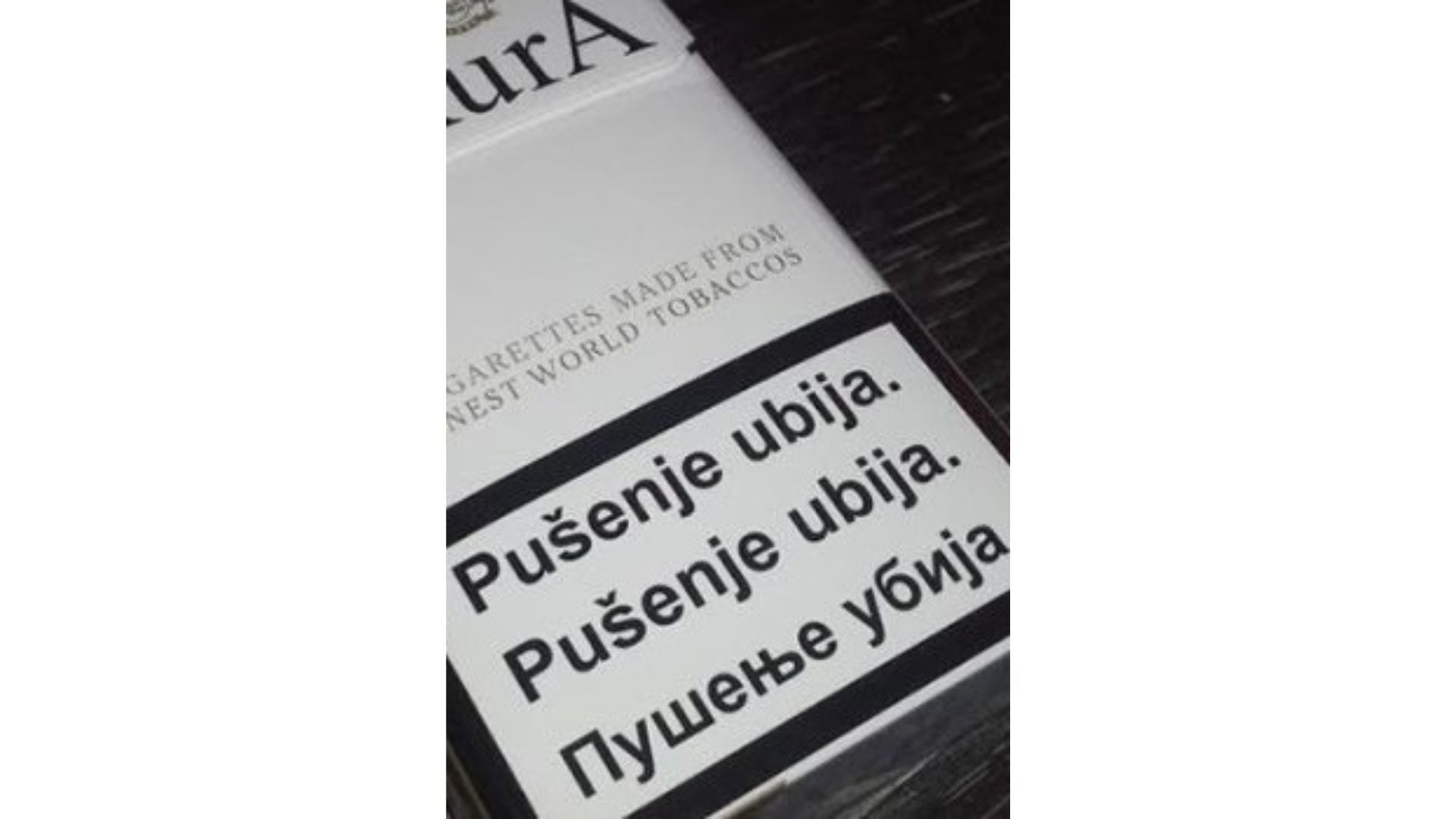

A few decades ago, the languages today known as Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian were considered a single language, Serbo-Croatian. When Yugoslavia fell apart, so did the idea of a unified language.

Key word being “idea,” because the speakers of Serbo-Croatian’s current successors still understand each other completely in speech, and almost always in writing. But the name of the thing is sometimes just as important as the thing itself. The question of whether these are four languages or simply dialects of one language is a topic of ongoing debate.

Dialects can gradually branch off into their own fully-fledged languages from geographic isolation. That was definitely not the case here. Renaming the language was a way of claiming it as one’s own and not anyone else’s, regardless of any objective linguistic reality. This is a bit like if the United States were to decide that the country will no longer use the English language but instead adopt the more patriotic “American language.”

Language and Ideology

Just as politics played a role in breaking up Serbo-Croatian, it also helped spark its unification in the first place. In 1850, two linguists —one Serbian, one Croatian— led the formulation of a “literary agreement” around a set of grammar and orthography conventions that later formed the basis of standard Serbo-Croatian.

Notably, these linguists all shared a common political goal of greater national unity among the South Slavic peoples, a school of thought that would soon evolve into Yugoslavism. Their document opened with the assertion that “one people need one literature.”

Once you make the association of nationhood with a single national language, it’s hard to put the genie back in the bottle. The same logic that once brought the language together would later be used to divide it.

Hindustani, Hindi and Urdu: A Colonial History

The situation is strikingly similar with Hindustani, an umbrella term used for the Hindi and Urdu languages as well as a range of colloquial registers that lie somewhere between the two, all of which are mutually intelligible in spoken form. Even today scholars often refer to Hindi and Urdu as “one language with two scripts,” separated mainly by modern political and religious identities.

The separation began in the 1800s, a period when British authorities in northern India were constantly tinkering with official language policies around local variations in speech and writing. Their efforts at standardization ended up sparking a bitter rivalry over which variety, Hindi or Urdu, should be the official language of education and administration.

Advocates of both Hindi and Urdu positioned themselves in relation to the elevated status of English under British rule, each seeking to expand linguistic influence by promoting theirs as the more legitimate historical language of the people. Hindi in particular also came to be strongly associated with the Indian independence movement.

In time, appeals to non-Western or non-colonial tradition would dovetail with religious demarcations associating Hindi with Hindus in North India, and Urdu with Muslims in Pakistan.

The linguistic divide grew in symbiosis with political developments that would lead to the eventual 1947 partition of British India into India and Pakistan along religious lines.

Print Media and the Power of the Written Word

The main contention was over the writing system: Devanagari-written Hindi versus the Perso-Arabic script of Urdu. For a long time, this was a marginal distinction. Script use did not always correlate to dialect or language, and most literature was passed through oral tradition anyway.

But as new technologies enabled the spread of print media, written language became a far more powerful tool of influence. The first stages of the Hindi-Urdu rivalry took place primarily in journals and newspapers, as well as educational institutions. Mass-produced literature facilitated the mass production of a standardized language (or dialect, or register, or… you get the point).

The Chinese (Counter)example: Political Cohesion as Linguistic Unity

The “dialects” of Chinese are in some ways a mirror image of the two earlier examples. The main varieties of Chinese are not mutually intelligible and certainly much further apart than, say, Serbian and Croatian or Hindi and Urdu, but remain united under the cultural banner of China and the Chinese language.

Mandarin and Cantonese, for example, are said to be around as different as Portuguese and Spanish. Yet while many European nations redrew their borders throughout the centuries, China continued to, for the most part, maintain cohesion as a single political entity.

Still, Mandarin was only standardized as a national lingua franca in the last hundred years or so, with the goal of national unity.

Navigating Dialects as a Language Learner

National or regional dialect distinctions are common among a wide range of languages — Spanish and Arabic being the best known, along with German and the Scandinavian languages (Danish, Norwegian, Swedish).

Additionally, almost every language has a more formal, standard variety that is taught in most textbooks and learner-oriented materials. This official standard can sometimes differ wildly from how the language sounds in daily conversation.

Start with the standard version of the language

As a language learner, there’s nothing wrong with starting with the standard language, which will have more resources available for self-study. In fact, this is almost always the recommended method. Even in remote areas, most native speakers know how to converse in both standard and regional dialects, having learned the more formal standard at school.

But you can (and should!) still work on comprehending the local dialect(s) of your interest, even if you can’t fully replicate them yourself. You only need to know how to say something one way, but you need to be able to understand all the different ways it may be communicated to you.

As a beginner, focus on just one language or dialect

The one you choose is up to you, of course, but avoid switching it up for at least the first few months until you get to a comfortable A2 level. It will be much easier to decipher the nuances between various dialects once you have a solid foundation in one of them.

This is the same logic behind avoiding “resource overload” at beginner stages. It’s better to choose one or two methods and stick with them to the end, rather than starting seven different textbooks and never finishing any.

Unless…

One big exception to the above is if you are learning a smaller language or dialect without many learning materials. In this case, even as a beginner, you may want to incorporate additional varieties that offer more robust resources for self-studiers.

Learners of Bosnian and especially Montenegrin will struggle to find sufficient resources without supplementing their studies with better-established Serbian and/or Croatian options. Some Urdu learners selectively use Hindi materials for grammar review or listening comprehension. Valencian learners might fall back on more widely available Catalan courses. With smaller languages, it’s hard to be too picky.

A word of caution: this method only works when there’s sufficient overlap in both grammar and basic vocabulary, which does not always correlate with mutual intelligibility. Afrikaans and Dutch, for instance, are largely mutually intelligible but have too many fundamental grammar differences for learners to be able to mix resources effectively. For example, Dutch has three grammatical genders, while Afrikaans has none. The same is usually said for Czech and Slovak, where differing verb conjugations would likely confuse beginner students.

Talk with native speakers, regardless of their dialect

These in-person interactions are typically the most rewarding moments in any language learning journey, so cherish the opportunity!

People all talk differently anyway, depending on age, class, social circle, and myriad other factors beyond regional or national background. Be ready for diverse, even conflicting opinions on grammar and vocabulary from both your teachers and everyday speakers — this is the reality of languages, which are always shifting and evolving, even if some would prefer that they didn’t.

Don’t worry too much about using the “wrong” word. Most people really will not care, especially since you’re learning the language from scratch. That said, you’re probably better off not disputing any “corrections” you receive, even if you know that it’s actually only a regional distinction.

As an intermediate learner, introduce more regional variety

Now that you have a base in the language, it would be a shame to miss out on its full cultural breadth. If you’re studying a language on Glossika with multiple regional or national variants available (including Arabic, Croatian/Serbian, Portuguese, Spanish or Vietnamese), consider choosing one course for focused study while dabbling in another on listening-only mode, selectively introducing specific topics for passive familiarity.

Once you begin absorbing content in your target language, you’ll also find that these national or regional delineations are not so clear-cut after all.

Reggaeton from Latin America is heard all over Spain. Bollywood films from India enjoy a massive following in Pakistan despite official government bans. North Koreans risk prison to watch smuggled South Korean dramas.

Conclusion

Who gets to define a language? Government officials? Academics and writers? Our contemporary reality shows a murky mix, but as learners, we would do well to consider the biggest group of all: everyone who uses it.

Whether it’s the songs they sing along to or the people they talk to, it turns out that native speakers rarely confine their language to strict geographic borders. Learners shouldn’t, either.

Interested in learning more about dialects?

- The Diverse Voices of Korea: An Exploration of South Korean Dialects

- The Future of Taiwanese Hokkien in a Mandarin-Dominant Taiwan

- Differences Between Kurmanji (Northern) and Sorani (Central) Kurdish

- Follow us on YouTube / Instagram / Facebook / Twitter