Have you ever thought of learning a “dead language”? It may sound like a waste of time since no one speaks it anymore.

Latin can help you to study not just Romance languages like Italian and Spanish but even German. German is actually among the modern European languages whose grammar is most similar to Latin. In this post I'll talk about studying Latin and how it's connected to modern European languages.

The cultural legacy of ancient Rome

Together with ancient Greece, Rome is arguably one of the cultures at the roots of today’s Western world. The impact of ancient Romans on modern political structures, as well as on philosophical and literary thought, is impressive. Try reading Cicero’s De Re Publica, and you’ll find reflections on the concepts of ideal government and justice that are no less relevant today than they were centuries ago. The word “republic” itself comes from the Latin res publica, meaning “public affair.”

In Res Gestae, Emperor Augustus describes in the first person his accomplishments, presenting himself as a just and magnanimous leader. This text provides a unique testimony to how the emperor built his political persona and is still worth analyzing today to reflect on the mechanisms of propaganda and leadership.

What about Stoicism? You’ve probably heard of this philosophical school, but you may not know that, although it originated in ancient Greece, it was ancient Rome that embraced this philosophy and brought it to its fullest expression. Seneca’s De Brevitate Vitae (On the Brevity of Life) is a passionate and timeless reflection on how to best spend the time you have and how to live according to nature’s principles.

And if you’re more of the romantic type, you can’t miss Catullus’s love poems for his beloved Lesbia (he’s the one who coined the world-famous expression “Carpe diem!”). Let’s not forget the epic: in Virgil’s Aeneid, a powerful female character, Dido, takes her own life after being abandoned by the hero, who had to pursue his mission of founding what would later become the great Roman Empire. Anyone who’s ever had their heart broken can’t help but shed a tear for the image of the mighty Queen of Carthage, who cannot bear the injury to her dignity and prefers to kill herself rather than live with heartbreak and dishonor.

How to study a language no one speaks today

When studying a language that only exists in written form, there are some significant differences. Much more emphasis is put on grammar and translation than on conversations and communication. Translations are usually only done from Latin into a modern language since there’s no point in translating something into Latin.

This kind of study focuses more on the explicit knowledge of grammar rules and structures. While learning English or Spanish, you may aim to improve your conversation skills and not always worry about getting the verbs and prepositions right. But with a language like Latin, the fastest and most effective way to approach written texts is by really getting confident with grammar because many conversational clues — context, mimic, tone of voice — are absent. This necessity to become confident with grammar is at the same time the greatest challenge of learning a dead language, but also the main advantage because the grammar systems and structures you learn may come in handy when learning other languages.

The cultural references are completely different from those we’re used to: familiar situations like “At the restaurant” and “Booking a hotel room” are going to be replaced by much less frequent contexts like “In the senate” and “At the temple.” That makes for a good challenge!

The two tools that are going to guide you through the mysteries of ancient Rome? A good grasp of grammar and a close relationship with the dictionary will provide you with a variety of examples and help you notice all the different meanings the same word can have when used in different situations or collocations.

Those two skills are going to be dramatically helpful when learning modern languages, too.

This may not sound like a lot of fun to many learners, but do you know what may change your mind? The relationship Latin has to modern languages, many of which inherited a lot from it.

What modern languages inherited from Latin

Here are some grammar structures, vocabulary elements, and general characteristics Latin shares with four of the most widely spoken modern European languages (apart from English): French, Spanish, German, and Italian.

Declension of nouns and use of cases

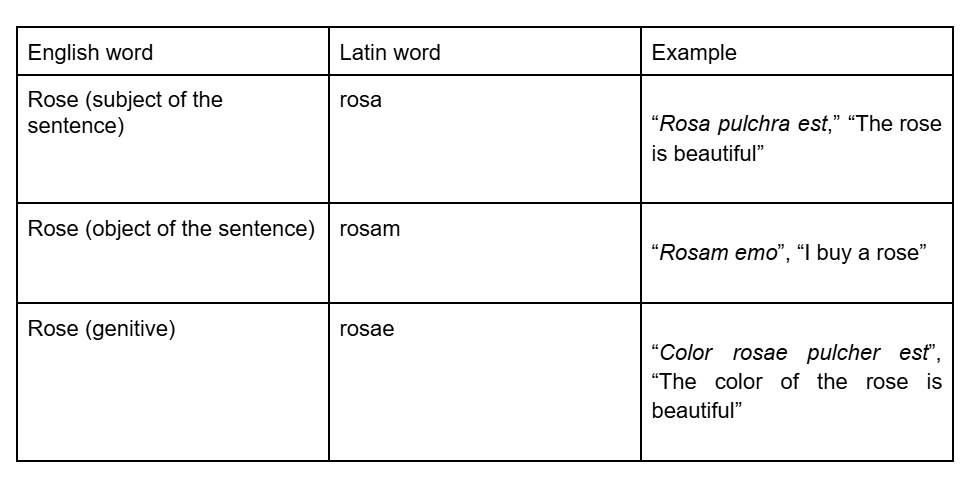

In Latin, a noun can be declined in four different cases based on its grammar function in the sentence:

If you’re an attentive reader, you may already have found out something peculiar about Latin: it has no articles.

The identical declension system is still in place today in the German language, but with a difference that makes it even more complex: not just the noun but the article too varies based on the grammar role the word plays in the sentence.

In some cases, the difference is only visible in the article: “Die Rose ist schön,” “The rose is beautiful” becomes “Die Farbe der Rose ist schön” in the genitive.

In other cases, the noun changes too: “Der Student ist nett,” “The student is nice,” but “Das Buch des Studenten ist rot,” “The student’s book is red.”

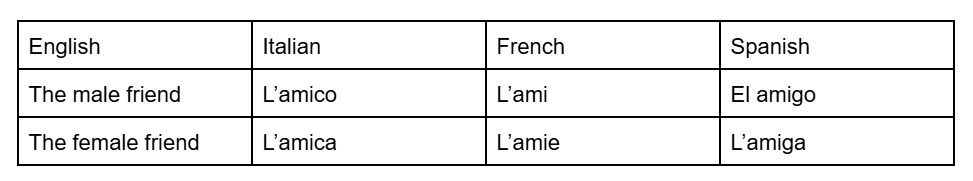

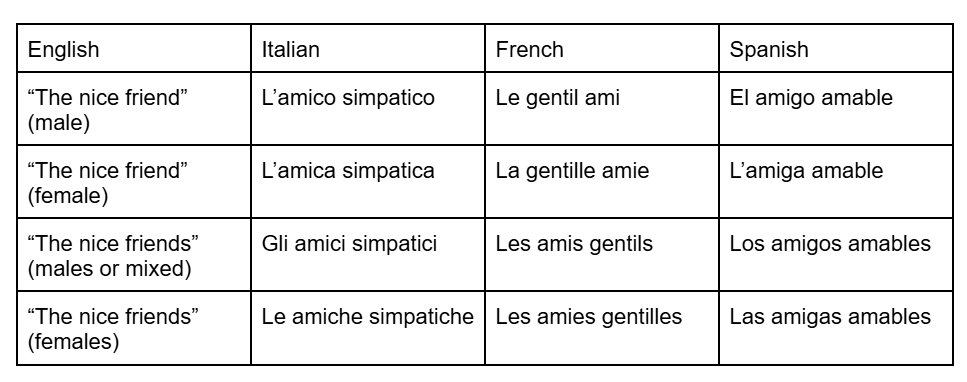

In Italian, French, and Spanish, there are no grammar cases, meaning that the noun itself and its article don’t change based on their role in the sentence. However, nouns are still declined for gender and number and are generally accompanied by different articles:

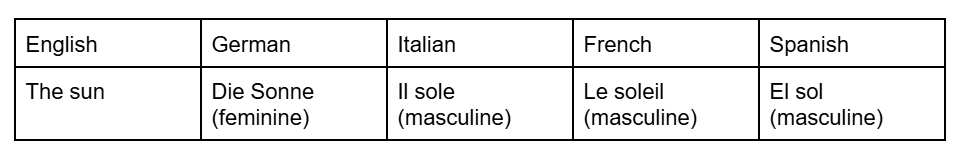

Not only nouns that refer to people or animals are gendered, but also those that describe objects with no obvious masculine or feminine characteristics. That’s why you should always learn new nouns together with their articles in Italian, French, German, and Spanish. Unfortunately, there’s no general rule. And here’s something even more surprising (and frustrating!): the gender of nouns isn’t always consistent across these languages, as shown below:

Latin nouns are gendered too. Not only that, but in Latin, there are not just two, but three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Of all the modern languages we’re analyzing, only German retains the neuter, as evidenced by nouns like “Das Buch” (the book) or “Das Auto” (the car). An ironic note: “das Mädchen,” meaning “the girl,” is actually neuter, not feminine!

Declension of adjectives

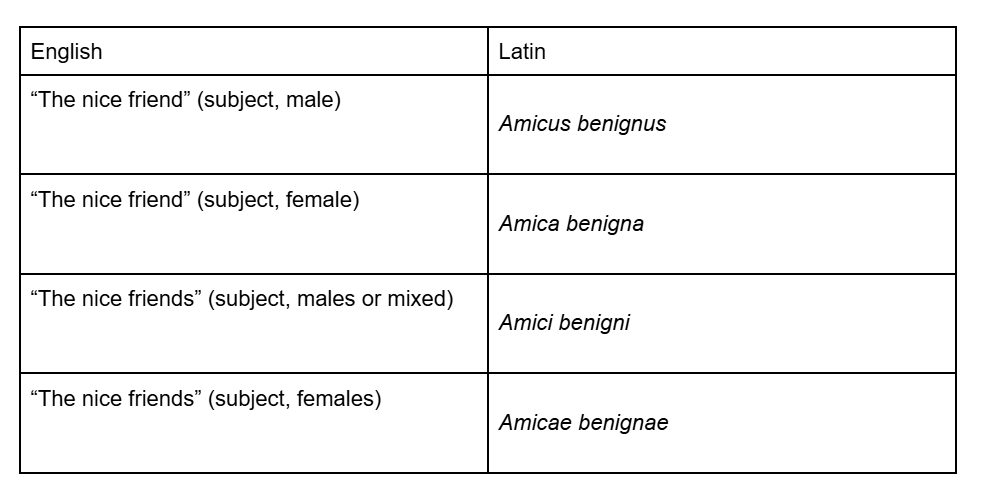

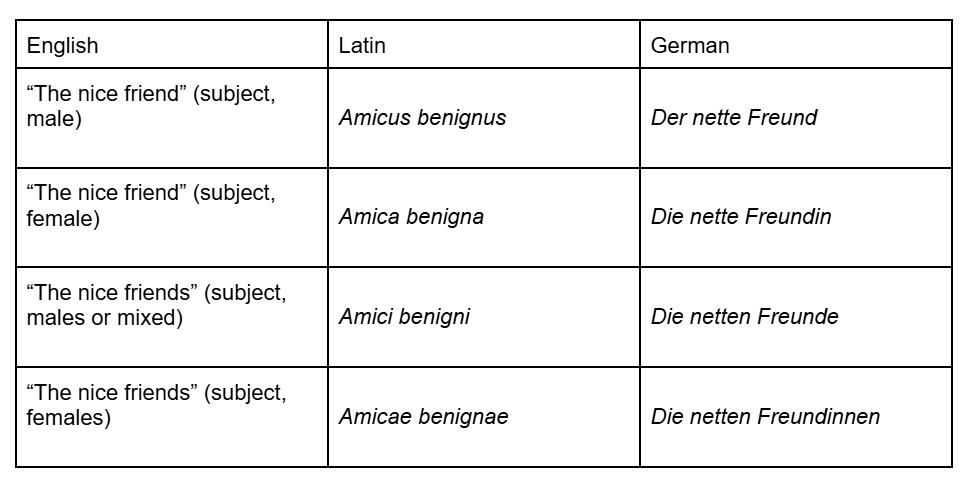

Just like nouns, adjectives also change based on gender, number, and case in Latin, as well as in German. In Italian, French, and Spanish, only gender and number play a role because there are no cases.

In English, we only decline nouns in terms of number (singular and plural), while adjectives are invariable: we’ll say “The nice friend” if it is singular and “The nice friends” if it is plural. We don’t care if the friend is female or male, nor do we worry about whether they’re the subject of the sentence, the object of the verb, or play a different grammar role.

Now, let’s take a look at Latin.

All four were written assuming the friend or friends are the subject of our sentences. If they’re the object or part of a complement (for example, a genitive), both nouns and adjectives take a different suffix!

The same happens in German:

If the friend or friends are no longer the subject of the sentence, articles, adjectives, and possibly nouns all take a different suffix. Funny, isn’t it?

In Italian, French, and Spanish, we don’t need to worry about the grammar role of the friends, but we still need to take their gender and number into account:

Verb tenses

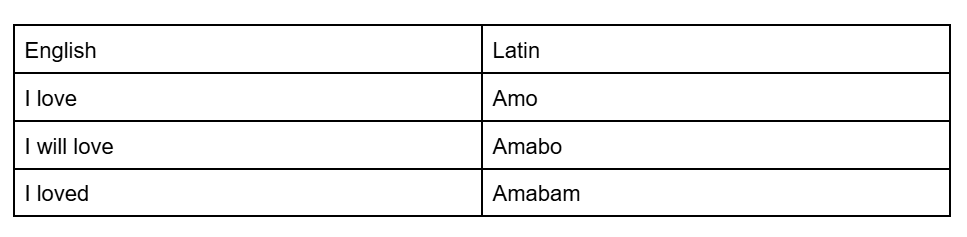

Latin has a complex system of verb tenses: present, three different forms of past (imperfect, perfect, pluperfect), and two futures (simple and perfect). All of them are composed of a single word built with different specific suffixes, for example:

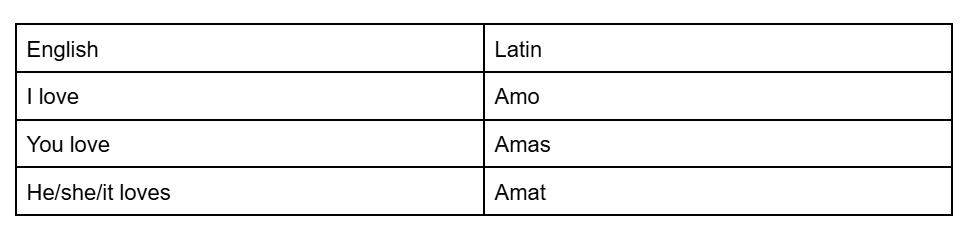

Verbs change depending on the subject:

This is true for all verb tenses. Thanks to these differences, in Latin, you don’t need to always express the subject like in English (the same holds for Italian and Spanish).

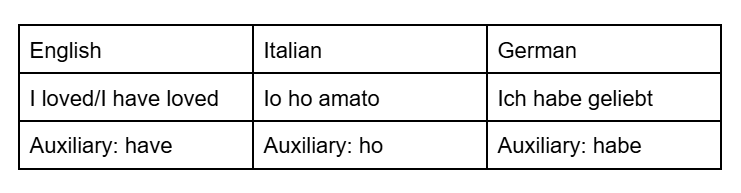

The verb system in the modern European languages we’re analyzing differs from the Latin one, especially in that they employ auxiliaries to form compound tenses. Let’s have a look at the past in Italian and German, for instance:

However, both Italian and German resemble Latin in the fact that verb forms change depending on the subject, unlike in English (“Io ho/Tu hai,” “Ich habe/Du hast,” “I have/you have”).

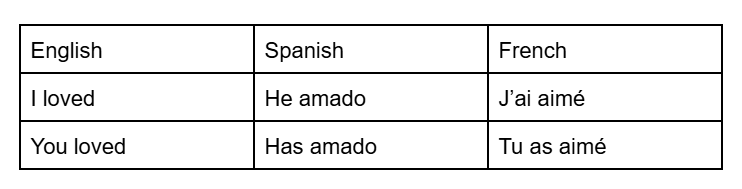

The same happens in Spanish and French: both use “have” as an auxiliary and change form according to the subject.

Note that all four languages can use both “to be” and “to have” as auxiliary, depending on the verb (for example, in Italian, “Io ho mangiato,” “I have eaten,” uses “to have” as an auxiliary, but “Io sono andato,” “I have gone,” uses “to be” as an auxiliary). The auxiliary “to be” is mostly used with verbs that indicate movement or a change of state, like to go and to grow, but there is no fixed rule.

Subjunctive for hypotheticals

Latin used the subjunctive mood to express wishes, possibilities, doubts, and actions not realized.

The same happens today in Italian, German, French, and Spanish, while it’s less common in English: the verb in the hypothetical if-clause “If I had money…” in English is the same we would use in a sentence that expresses a reality in the past: “I had money.”

The distinction between reality and hypothesis is only evident with the verb “to be”, in fact, we say “I wish I were rich/If I were rich…” and not “I wish I was rich/If I was rich…”

Instead, in Italian, German, French, and Spanish, the distinction exists for all verbs. For example, to say “If I had money…” in Italian we would say: “Se avessi soldi…” (subjunctive) while “I had money” translates to “Avevo soldi” (past tense).

However, there are differences in the way we form a hypothetical sentence. In Latin, we would use subjunctive in both the if-clause and the main-clause because Latin has no conditional: “Si dives essem, multa dona darem” (“If I were rich, I’d give many gifts”). The same happens in German, with the double use of Konjunktiv II: “Wenn ich reich wäre, würde ich viele Geschenke geben.”

On the other hand, French acts a little differently because it has a subjunctive mood, which is used to express doubts, necessities, or unreal conditions, but in an if-clause, it uses the equivalent of the past as English does, while it employs a conditional in the main clause.

Finally, Spanish and Italian employ subjunctive in the if-clause and conditional in the main clause, for instance: “Si fuera rico, daría muchos regalos.”

Order of the elements in a sentence

In English, the order of the elements in a sentence is rather rigid, exactly because the declension is so meager: we can only say “The dog eats an apple” and not “An apple eats the dog” because if we vary the order, the meaning changes.

Thanks to grammar cases, however, Latin doesn’t have to worry about misunderstandings: if “the dog” is in nominative (the case of the subject) and “an apple” is in accusative (the case of the object), we can safely vary the order without altering comprehension.

The same happens in the German language. However, in a German affirmative sentence, the verb must usually be at the second place. The order of elements in a sentence also varies depending on whether it is a main clause or a subordinate clause.

Spanish, French, and Italian no longer have cases, which means that the sentence order is rather rigid.

Vocabulary

A lot of words we use every day come from Latin! Let’s take a look at some examples from various categories.

- Medical lexicon: Did you know that “medicine” comes directly from the Latin word “medicina”? So do the Italian “medicina”, the French “médecine”, the Spanish “medicina”, and the German “Medizin”.

- What about politics? Words like “senate” and “congress” come straight from their Latin counterparts “senatus” and “congressus” (Italian: “senato, congresso”; French: “Sénat, congrès”; Spanish: “senado, congreso”; German: “Senat, Kongress”).

- The names of many job titles come from Latin, like “engineer,” from “ingeniator”, “he who invents”, or “professor,” from “professor”, “he who teaches” (Italian: “ingegnere, professore”; French: “ingénieur, professeur”; Spanish: “ingeniero, profesor”; German: “Ingenieur, Professor”). The -or suffix is in fact used in Latin to indicate the person who performs the action: from “ingenio”, “to invent”, we get “ingenior.”

- In the economic field, from the Latin “mercatus” and “creditum” we get our “market” and “credit” (Italian: “mercato, credito”; French: “marché, crédit”; Spanish: “mercado, crédito”; German: “Markt, Kredit”)

These are just some examples. Do you still think Latin is a dead language? Think again! Even our words for “computer” come from the Latin verb “computare”, “to calculate!”

Prefixes and suffixes

Many prefixes and suffixes we commonly use in our languages come from Latin. Just to mention some examples:

- “anti-” to indicate the opposite of something: antibody (English), anticorpo (Italian), Antikörper (German), anticuerpo (Spanish);

- “re-” or “ri-” to indicate a repetition: reread (English), rileggere (Italian), relir (French), releer (Spanish)

- “dis-” or “un-” to negate something: disagree (English), disaccordo (Italian), désaccord (French), disacuerdo (Spanish); disconnect (English), disconnettere (Italian), desconectar (Spanish), déconecter (French);

- “pre-” to indicate that something comes first: prepare (English), preparare (Italian), praparar (Spanish), préparer (French).

Final take

That’s a lot to take in, isn’t it? And we’re just scraping the surface! It’s fascinating to explore how closely connected languages are. All this complexity may seem discouraging at first, but if you think about how many similarities and recurring structures are there, you’ll easily see that the more you learn, the easier it gets!

Latin is directly or indirectly at the root of many European languages, so knowing Latin will make it easier for you to recognize and understand the grammar structures you’ll encounter when studying other languages.