The Most Powerful Memory Method

Well OK, maybe not the most powerful memory method, but certainly a very powerful memory method that works for me: spatial memory. I'm going to be showing you how you can use spatial memory for yourself to significantly improve your language learning efforts.

If you've been following my work, you might be aware that I regularly study languages from around the world. To remember all of those languages effectively, I keep a mental “Google Earth” in my mind — spin it around, zoom in on a place, and look at the language information that I've stored there in my mind. I want to share with you my “mapmaking” memory technique — not specific to but well-suited for language learning — I call it geolocating, and it's a lot like using a GPS or Google Maps to get around town or around the world.

Contents

Mapping and Memory Anchors

Geolocating: Not Just For Languages

Language Geolocating: Taiwan

Geolocating by Experience

Your Mind, Your "Memory Palace"

2021 Update: Memorising Pi to 1500

Mapping and Memory Anchors

The visual representation of a map and visual images of the country are the first kinds of memory anchors that I use. For example, there are more than a hundred languages that I've studied so far. Most people would be hard-pressed to even name 100 languages. However, I use my knowledge of the layout of the land to remember not only what languages there are, but even down to the nitty gritty details such as vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar.

I'll start with an example of something that is easier, then I'll give an example of something more challenging. The first example is using national borders. If you ever get the chance to travel, make good use of your experiences by taking pictures or keeping a diary of what's happened on the way. And always look at maps to see where you are, where you're coming from and where you're going.

If you're taking a road trip through Europe starting in France and heading east, it's physically impossible to end up in Poland next. You have to pass through Germany first. If you head south from Poland to Hungary, you're most likely going to go through Slovakia, then entering Vienna in Austria, before passing the border again into Hungary. If you remember your road trips, you'll remember the locations of all the countries very easily.

Can't do the road trip, you say? Turn on Google Earth, rotate it with the horizon up ahead and start exploring! It's not just a great tool for browsing, it can do absolute wonders for your map skills. Most maps are positioned with North at the top, but you really need to have the ability to put yourself anywhere and know what's around you. It should become second nature that when heading south through Slovakia that you know Czech is on your right-hand side. Google Earth can help immensely with this.

I learned these skills as a child (before the Internet) taking road trips with my family all over Europe. And my curiosity of mapping our every location has built some incredible skills that I could not have foreseen.

I know many people, especially those in my close family, who have terrible map skills, and to use a cute term, it's what the Chinese readily acknowledge themselves as road-dumb (路癡 lùchī). I often get asked how I do it because for them the hard part is remembering the map itself. But if you integrate maps into your daily life by always looking at where you are and where other people are, maps will start to become second nature to you. In fact, with the internet today it's a snap to simply check out the map on your phone when you're out and about. Start with your own city, and figure out what landmarks are “anchors” for you when you move through the city. Expand your search to your state, region, or country, and pay attention to the anchors that guide your memory. If you want to try this method, understanding and recalling maps is critical for the real meat and potatoes of my favorite spacial memory technique: geolocating.

Geolocating: Not Just For Languages

Jan van der Aa, a friend of ours in the polyglot community, does a lot of traveling. This year he's traveled to several countries in West Africa, and in just the last couple weeks he's made his way to Norway, Svalbard, Kazakhstan, and now Hong Kong. I have many acquaintances online that are traveling constantly wherever business takes them. Friends from Taiwan might be on vacation in the Pacific, in Indonesia, in the Maldives, in Europe, or studying abroad in the US. How do I know that?

The same way you do — Facebook!

When I see a post or a status message from so-and-so landing in such-and-such a place, I stick their Facebook pin on my mental map and they are geolocated in my mind. I can even rewind back through the past, but I might obscure the actual dates. (On the other hand, Jan travels so much that I don't think I'll ever be able to keep up with all the details of his travels!)

So the first and most essential map skill is being able to geolocate whatever you read or hear about on your mental map. Even if your map skills are not that good, the regions on the world map below should be recognizable to you. At least you should be able to recognize the continents. As time goes on, try to get more and more specific and find out locations within those continents and their general position to other points you have already learned.

From left to right on top: North America, Europe, Asia.

From left to right on bottom: South America, Africa, Australia.

In my case, one of my mental maps has little bobbing Facebook profile pictures of my friends scattered around the world. I've been doing this for a long time with all different kinds of data, and you can get started right away with whatever data is handy! Once you can identify individual countries on the map, see if you can start geolocating your friends, family, or some other type of information that's important to you on your mental map. If you see a friend update their status about a particular place, read about something in an article or on a blog, or hear something on the news: stick a pin in your mental map, and try to connect those place names to the actual places that are anchored in your mind.

One key point to bear in mind for this technique (or any memory technique, really) is that the more relationships you can find between your data, the easier it will be to remember. Familiar faces, Facebook status messages, and news clips can all be used as easy-to-remember data points that build on one another and make it easier to remember your mental map. Remembering where you or your friends have been on a map is interesting, but many years ago I discovered one use case for geolocating that has thus far yielded absolutely incredible results: language learning.

Language Geolocating: Taiwan

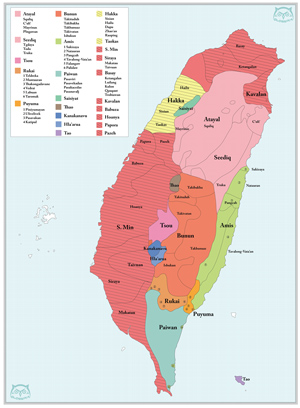

A few years ago I decided to learn as much as I could about the indigenous languages of Taiwan within a limited amount of time (there was a video called 18 languages in 4 months). I had a slight advantage since I live in Taiwan. I was curious though how much Taiwanese themselves are familiar with these languages and I discovered that just a casual face-to-face interview with average Taiwanese citizens revealed that most Taiwanese cannot name more than 3 indigenous languages.

How then was I going to learn about 18 languages, not to mention make sense of the 42 different dialects spread among them (I would have to choose and focus on at least one dialect of each language).

I started with geolocating everything. Of course, there are no national boundaries to define in this case, so the task was more complicated. And maps with colored areas of the approximate locations were not specific enough. No, I needed imagery of the people, of their villages, the real, actual locations where people used these languages.

One part of this mission involved traveling around Taiwan visiting various locations. Even if I couldn't actually get to tribe I wanted to visit, I'd at least have the experience of going, or being in the vicinity, and having memories of that experience itself. You have to bring it to life somehow with more sensory anchors.

Here's an example of how I remember my travels, to give you an idea of the kinds of anchors that guide me and the kinds of things I geolocate on the map:

Just south of Taipei, you reach the Atayal tribe of Wulai. A bit further south and west is a remote village called Smangus (in Xinzhu), another Atayal-speaking tribe. Heading south is Nanzhuang in neighboring Miaoli which is home to many Hakka Chinese speakers, and also the majority of Saisiyat speakers, several of whom I met with. Heading south across a mountain range I come to a town called Wenshui, and turning left on to a country road leads up to the Atayal Mayrinax-speaking area.

Further south in the city of Taichung heading left (east) into the mountains, there's a valley where the city Puli is located. This is also home of the Pazeh and Kaxabu speakers. Heading straight east up the mountains takes you to Seediq and Taroko territory. But if I turn right from Puli I arrive at Sun Moon Lake, home of the Thao. I had geolocated so many different languages, and that was all on a single trip!

South of Taichung, you arrive at Chiayi. Located at the base of Alishan mountain, Chiayi is famous for its tea plantations. Heading up the mountain you come to a valley of Tsou (Cou) villages, memorable for the strange consonant clusters in their village names, like Tfuya. I've taken the trip across Alishan back and forth a few times by now, and if you come from the north (heading south from Sun Moon Lake), you can visit the Bunun-speaking valleys. The road after that is a pretty hairy experience, but the road conditions even helped reinforce my memories of the area.

South of Alishan, you pass through the beautiful winding roads of Siraya National Park (named after a language that is currently trying to be revived), and eventually come to a large lake. Passing around the north end of it and crossing another mountain range on which there are many tea-selling Tsou, you'll arrive in the isolated Namaxia valley full of Kanakanavu villages. This place has proven to be the most difficult place to get to in all of my travels particularly due to the devastation after Typhoon Morakot on Aug 8, 2009.

Further south still, you'll find a village called Jiaxian. First try their famous taro ice cream (it's delicious!) then turn left, head over a mountain range and you'll arrive in Gaozhong where the primary contact speaker of Saaroa (Hla'arua) is a high school teacher. Heading south out of this valley, you can turn east up into the mountains at Maolin, and you'll come across three Rukai villages all speaking their own languages: Teldreka, Oponoho (Mantauran) and Thakongadavane (in that order). The next entry into the mountain range brings you to the main Rukai language spoken in Wutai village...

And that's just the west side of the island! There are another dozen locations on the east side of the island.

Geolocating By Experience

I hope you enjoyed my short travel diary, but I also hope you get a sense of my main point: each of the locations on my journey represent not only an experience with all of the sights, sounds, smells, and people that make up the experience, but also a geolocation. My interactions with people, the stories they told, even the different kinds of food I ate, like takith which is the Thao word for muntjac (山羌), become more anchors that allow me to remember even more detail about the languages of the people I met.

In this example, the Taiwanese aboriginal languages are not really spoken over an area of land; they're spoken at very specific points on a map, which usually comes down to a handful of people. I won't discuss my reasons for learning such tiny languages here (but if anyone is interested I'd be happy to write a post on it!), but let's suffice it to say, looking at the maps of where the languages are located is nothing compared to actually traveling and meeting the people face to face. In a pinch, though, or when you're just getting started, looking at the maps (or flying around Google Earth) is certainly better than nothing.

Basing my studies out of the university library in Taipei where so much language documentation can be found (I recommend National Taiwan University's dedicated Library of Aborigine Studies and Academia Sinica's excellent library in the Arts & Humanities Building), I now had the tools to geolocate every piece of data I read about any of the languages. I also geolocate language data vertically regarding nouns, verbs, and other parts of speech. I also read about the history of the language family to create more connections and memory anchors that are linked through time. And now recalling this experience, I would often come across tidbits about languages from other parts of the world: something on Egyptian Arabic, something on Uyghur, something on Armenian, something on Frisian, and immediately those tidbits of information would be geolocated and locked into my memory for future recall.

Having a way to organize your data vertically is also another topic entirely. But in the next few posts I will be talking a bit about one specific aspect that boosts our memory of vocabulary: the DNA of language (link pending).

Now if a Taiwanese person asks me about all the indigenous languages in Taiwan, and I list them off either in English or Chinese, it takes virtually no effort or recall because I'm just reliving the road trips around the island. I can do it in geographic order or I can even recite someone else's list in the exact same order they gave it (this is essentially the same as the Memory Palace memory system) because each location has a specific geolocation.

Finally, as a result of this amazing journey into the study of the Austronesian languages of Formosa, I've finally had the opportunity to meet the authors that I've spent so much time reading on Austronesian and Formosan linguistics including Robert Blust, Laurent Sagart, Li Jen-Kuei, Elizabeth Zeitoun (not pictured), Alexander Adelaar (not pictured), and Malcolm Ross. And I'm greatly indebted to Elizabeth for giving me the gift while visiting her office of her recently published the 600-page "A Study of Saisiyat Morphology" that has more example sentences and complex grammar tables than I've seen for Slavic or Caucasian languages: a truly massive œuvre de vive, and just one of her many.

Your Mind, Your “Memory Palace”

The world is a big place and if your memory palace is the size of the world, then you have an enormous amount of space in which to record new memories. Everything that happens in our daily lives happens somewhere in the world, at some spot on the map. Plenty of our experiences are easily forgettable, but when you see or hear about a place that you visited once — even if you think you've already forgotten it — you can probably recall approximately when you were there, what you did, what you saw, and who you were with.

Forgettable memories are those that come from things we do every day, in the same location, day in and day out. Rewriting new memories on top of old ones in the same place so frequently squishes them all together and they become a blended blob of vagueness. Have you ever forgotten where you parked your car because you park in the same lot every day? I do at least once a week. But I'll never forget the many languages I encountered around Taiwan, and that is the real key: build your experiences in new places that use new languages, and you'll do much better at keeping them long term.

2021 Update: Memorising Pi to 1500

During pandemic lockdown here in Taiwan, which didn't occur until June of 2021, I tried out an experiment. If my spatial memory is so good, why not try to attempt something like pi? I've heard of people memorising it to astronomical numbers.

So, on three separate consecutive Sunday mornings, I memorised 500 digits of pi with very little effort. First, I mapped out a route on the world map, and associated the numbers of pi onto that map, starting from Portugal in the West all the way to southeast Asia in the East, assigning the numbers of pi to each country and using imagery of each country so that 0 = passing water, and 9 = a mountain or very tall building peak. There were some exceptions to the rule where I had to assign 693 to Belgium and 993 to Netherlands. But exceptions like that make the association even stronger, because you tell yourself: this is a big exception!

In only a couple hours of each of those Sunday mornings, I was able to assign to memory 500 digits of pi, and I did it by checking my work with a Pi app called Pi Trainer, which doesn't restrict the time it takes me to think or recall (really apprecaite that). By the end of the experiment, I was able to recall as many as 1600 digits of pi to as much as 97% accuracy (errors are deleted and fixed along the way... and I must admit that many errors were simply typing mistakes getting used to the speed at which the interface accepts my numbers).

The most surprising part of this experiment was that I could start at any point in the sequence and go forwards or backwards by simply walking the path in my mind.

The next set of experiments is to see how well such techniques can be applied to memorising hundreds of pages of piano music, and memorising full dictionaries with all the translations. It's an ambitious goal, but one I'm excited about in developing new features for acquiring vocabulary and foreign languages.

🚩 Try Glossika's Audio Training for Free

Whether you are a beginner or an advanced language learner, Glossika's audio-based training improves your listening and speaking at native speed. Sign up on Glossika and get 1000 reps of audio training for free -- no credit card required!

You May Also Like: